Honda Days Are Over, Now What?

It’s dark outside. Honda Days are over. I don’t know what to do. I want to call someone, but no one talks on the phone anymore. I know that’s negative speak, and I should try, but I’m afraid of rejection.

But that’s okay. Good vibes only, right?

Confidence and vibes, that’s how we survive. I read that at a gas station when I was ten. This graffitied wall really spoke to me.

If you’re confident, life can be anything you want it to be. You just gotta believe.

I worked Honda Days as a way to get some extra income for me and my wife, Dana. But my Christmas present was coming home for lunch and walking in on her having sex with our neighbor, Cheryl.

I didn’t want to overreact. I know I’m not much to write home about—a rabbinical school dropout who worked part-time at Honda.

Most people would flip out.

Not me.

As long as I stayed positive and understanding, this wouldn’t count as a crisis. This wouldn’t be a dagger twisting into my aorta.

Maybe this is something I could be a part of. Maybe they want me to join.

I took my khaki pants off, gave a smile, grabbed a bottle of Honda Days promotional shea butter from the nightstand, and offered to rub their shoulders.

Boy, I could not have read the room poorer.

Dana hurled insults at me. “Lumpy idiot” is one that has stayed with me. She said I looked like a hairy Oompa Loompa. But in her defense, I’m 5’5” and have red hair. Also, I was still wearing my powder-blue puffy North Face coat.

This was devastating. Not just because it was probably the end of my marriage, but because it was the moment I realized my parents raised me with too much confidence:

– I believed I could do anything.

– Be anyone.

– Everyone liked me.

My parents didn’t just tell me I was special—they held a ribbon-cutting ceremony every time I successfully digested a grape.

But looking back, there may have been some signs.

After college—when I made my first entrance into the real world—it slapped me in the face. Hard. Like, left a handprint.

The economy had just taken a giant dump.

There were no jobs.

The housing market was crashing.

The big banks were crashing.

I had student loans eating me alive, and a Discover card bill from senior year at an absurd 29.99% APR.

I had to pivot. If the world was going to take a poo on me, I would try to “Yes, And” that poo.

So I did what any normal person would do—I moved to Chicago and started doing improv.

What. A. Nightmare.

Sure, it was fun. Yeah, I loved pretending this was my future—that I would be the first person to ever make money doing improv. But as my life flashed before my eyes, half-naked in my puffy North Face coat, I realized improv wasn’t my dream—it was delay.

“I am an artist,” I told myself.

“This is what art is all about,” I lied to myself.

WHACK.

Life right-hooked me in the face. Again. Harder this time.

You can’t live in Chicago and pay bills when most of your time is spent pretending to be a beaver who works HR at the Sears Tower.

I had to declare bankruptcy. And the knockout punch was realizing I was not good at improv.

No big deal—I got this, I lied.

I collected myself and came up with a reasonable, practical plan.

Rabbinical school.

As I bent down to pick up my khakis, I realized it wasn’t a plan. I was running away—to hide from my shame and my creditors.

But there I met Dana in our first year. We married soon after.

Being a rabbi is hard. I couldn’t take it. My family was so proud of this idea of me.

They bragged to their friends: “They love him. Scott is going to be a big rabbi.”

But I just couldn’t believe this make-believe world and the crazy stories passed down for over 5,000 years.

I couldn’t do it. But I wasn’t going to let that define me.

Dana became a rabbi, and I got to be a stay-at-home husband while I figured out my passion—what I really wanted to do.

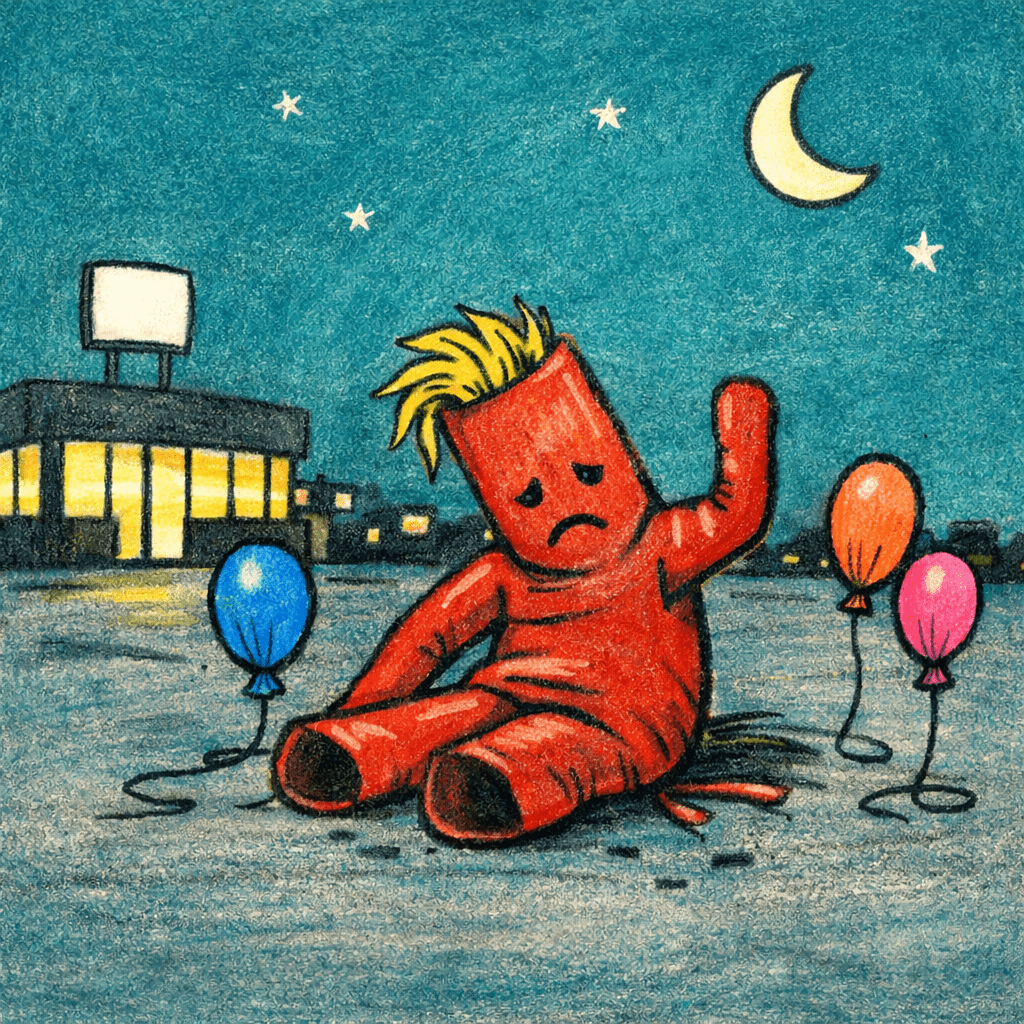

During Honda Days, the world made sense. The showroom was a place people came drunk with hope and enthusiasm. The giant inflatable tube guy was all of us—our own Honda Jesus.

Maybe I could write the next great novel. Yeah. That’s kind of the vibe I’ve always been giving off.

“Oh, did you read Scott’s novel? It’s so good.”

“Yeah, Scott is like our generation’s Kurt Vonnegut. Or Hemingway.”

I took a bunch of part-time jobs to absorb life around me so I could put it on the page.

And now Dana’s left me. Cheryl’s husband, Andy, avoids eye contact with me when I take out the bins. I think he blames me for this.

Honda Days are over, and I am left with this existence—no real future. Humiliated.

Confidence is the only thing I ever had. And now even that’s gone.

It feels darker than it ever has.

All of the balloons that remain in the showroom have deflated.

Honda Days are over.

Now what?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!